The Problem with Breath

On day 1, when my comrades and I talked about it, we couldn’t quite figure out how it happened. It just seemed as though we had suddenly been incited not to communicate or enact our love for each other. This time, no policy had been formulated, no law had been issued. It was harder than usual to locate where, to which parts of the apparatus, we should direct our attention.

On day 2, we were at a loss. We had gotten so good at reading the apparatus. We had developed wonderfully efficient techniques of resistance. Each and every one of us had become most brilliant at crafting discrete gestures of love. On day 3 onwards, we were misfiring on a regular basis, falling in and out of love with the same wrong comrades, over and over again, and always out of sync. The loving gestures we composed were barely legible and when we would intuitively find a genre in which to communicate our love, something would inevitably break down. Voices, generally. Sometimes the entire figurative system. Bodies, always. We would lose sleep and appetite over love and get useless for weeks.

And then, the problem with love became a problem with breath. On day 6, the air got hot and busy with ashes and all sunsets turned red. At every breath, for all we knew, we could be inhaling particles of carbonized pine sap, debris of melted trailer parts, or burnt baby birds in bits. I quit smoking. I bought boxes of white masks at the construction store. The dominant smell during these days was a cagey mix of ghost paint, polymer fibers, and dry chemistry.

On day 17, the air got cold and saturated with drops of viral poison. The city shut down. An incredibly sad number of lungs, too. The perspective to live in pods and die alone, disconnected from each other’s breath, hyper-connected to life-support machines, plunged many of us, myself included, into brand new strands of historical despair. For those of us whose lungs had been weakened by bad inner-city fumes, evil chemicals, or entire centuries of racialized exposure to horrendous air quality, the problem with breath became plain lethal.

Our neighborhoods were saturated with wildfire smoke and unnecessary death. Elsewhere, the streets were not empty. And when I say not empty, I mean they were just not. Or not yet. Usual metallic densities on the bridge. Geometrical glows of digital light in the underground.

Abnormally, no bodies of any ancestries were being captured, or hanged, or tortured, or kneeled upon. Nothing tangible, nothing blatantly repressive this time. No gas, no gag, no name, no whip, no rope. No strangulating remnant of sovereignty within no softness of biopower. A racist and classist brand of distributive pneumocracy is what it was, or at least this is how it initially appeared.

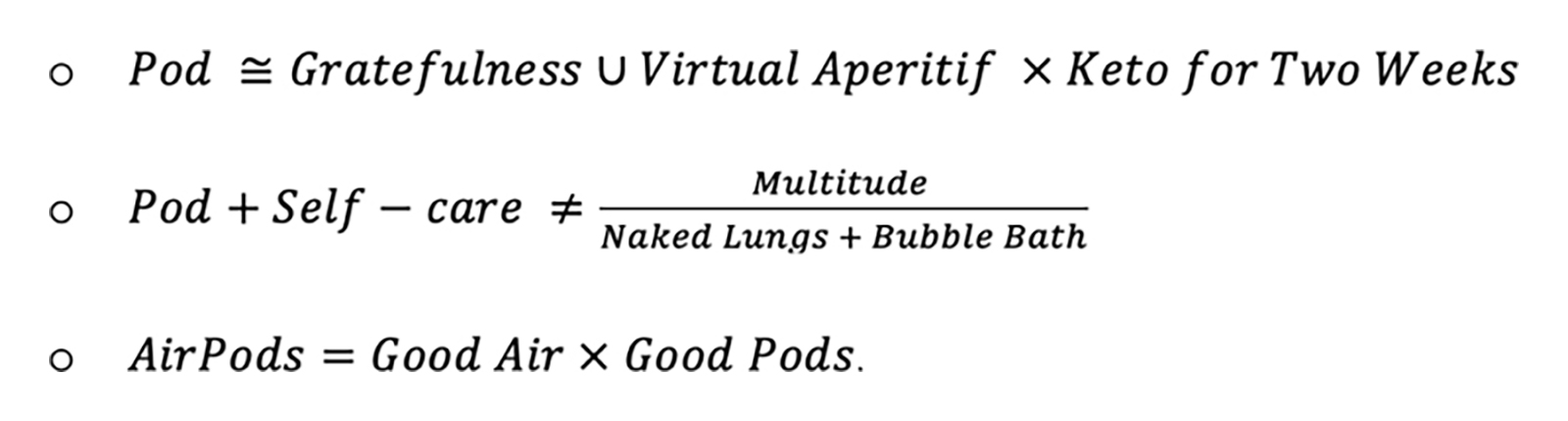

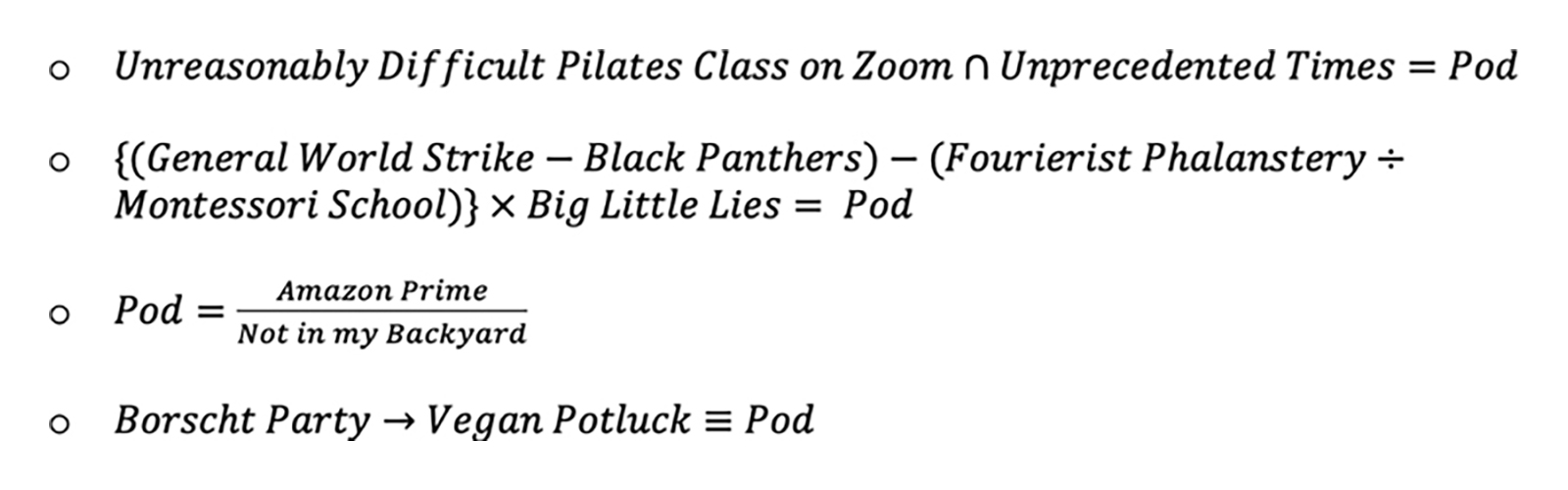

On day 25, “Critical Pandemic Studies” became a thing, and “Pod Theory” a subgenre in post-social anthropology. Denounced as a “white fantasy of networked individualism,” (in one of its purest forms) as “domestic fascism dressed as elective affinity,” the pod appeared to us, from the get-go, as a thoroughly ratchet social formation. On day 29, the “podtag” emerged as a timely intervention in existing forms of street art. Equational in its form, efficient in its power of evocation, and satirical in its poetic economy, the podtag proliferated on the privatized walls of neighborhoods where the biggest challenges presented to breathing were unreasonably difficult Pilates classes on Zoom.

On day 35, the air got complex and full of knots, so striated that we could no longer count on our capacity to share the same air. A meal was being cooked, an instrument was being played, a child was given birth to, and suddenly the rhythm of all breaths would break. Sometimes a pair of lungs would refuse, stubbornly, to take in any oxygen until someone else’s pair of lungs had released its own dose of carbon dioxide. At other times, the quantity of air available to each one of us would decrease with each increase in the number of conveners. Needless to say, we took these attacks on our collective breath personally.

On day 43, our conspiracy theorists inscribed these phenomena (air scarcity, divisive dyspnea, pulmonary stubbornness) within a longer genealogy of pneumatic State terrorism. Our allegorists, on their part, vowed to understand the situation as a logical and overdue meditation on the irrespirable. We were dying, hypoventilating, suffocating, mourning, for sure, but quite inspired, nonetheless, by the sophisticated constraints placed on our breathing.

“Stifled Realism,” one of us suggested.

“For what?” I asked.

“To name the weird brand of oppressed materialism that everyone has sunk into,” my comrade responded.

“Yeah. It works,” I answered. “For our asphyxiated symphonies. And our hyperventilated polyphonies. For our Afroapneic ecologies too,” I added.

“Yeah. It works for them, too,” my comrade confirmed.

“‘Pneumatic melancholia,’ maybe?” I suggested.

“As the main affect of stifled realism’s interdependent subject? Yeah, no.”

“Too tacky?” I asked.

“Too tacky.”

By day 41, we were full-time conspiring, acknowledging that with each gesture of creative love or bare persistence came the risk of being responsible for the asphyxiation of the other.

“If I cough,” I told one of my beloved comrades on day 42, “if I cough to dislodge bits of burnt baby birds from my bronchioles, if I have a fit of cough for whatever reason and your lungs are chiasmatically set on mine, then your respiratory system won’t know whether to inhale or exhale. Simply put, if I cough you die.”

“Let’s first bring the economy of hypotheses to a sub-paranoid level,” she suggested. “Then let’s talk cough drops.”

“But when I cough,” I said, “the legibility of my breathing impacts the possibility of yours. What if you die because I cough because of dead baby birds?” I asked.

“Hyper-causalism is a syntactical manifestation of delayed or anticipated trauma,” she declared. “You’re spooking yourself. Plus, dead baby birds are an effect, not a cause. Get a grip.”

“Are you calling me emotional?

“You shared your hormonal iCal with me,” she responded.

“Regardless,” I added. “At about any moment, our pairs of lungs can engage in about any morbid symphony. Random death is the stuff of trauma, delayed or anticipated.”

And we all started to wonder which part we had played in these failures to love, to communicate our love, to breathe the same air, to inhale and exhale, peacefully, without purpose, ad libitum.

“Failure,” one of us said, “is when struggle no longer seizes knowledge.”

“Failure,” it was offered, “takes when knowledge stops articulating love as struggle.”

“Failure,” it was added, “is whenever we start going aphoristic where we used to remain analytical.”

“Failure,” one of us responded, “is whenever we start going meta where we used to remain in it.”

“Failure,” I intervened, “is what happens to our entire respiratory systems before we die alone. ‘Failure’ is a lull into nothingness by the beeps and beats of outdated breathing machines, concretely.”

So “Failure” had become a thing. And it was sounding like a dysphony of competing positions and opposite intentions, around a bad concept, as it were.

“A bad concept is whenever an anti-revolutionary proposition takes up the clothes of negative dialectics,” one of us said.

“We declare we are not sure about the clothing metaphor in particular and metaphorical devices in general,” someone else declared.

“Negative dialectics is a bad concept,” a comrade jabbed.

“Bad concepts are Dad’s concepts,” I prolonged.

“There is no such thing as a bad concept, there’s only bad conceptualization,” someone else added.

“Let’s be clear about it,” a comrade concluded, “‘bad concept’ is when stuff’s not helpful.”

To counterattack, we thickened our strategic lines. On day 58, we went cartographic about it. To map out the attacks launched on our respiratory systems, we helped our cartographers disappear in the internets, in search of the most obscure contributions in counter-mapping warfare. From the cartographic undergrounds, they would emerge red-eyed, out of breath, just alive enough to sit at our debriefing meetings. Their cognitive functions were completely de-temporalized, their sensorial functions de-coordinated. Indifferent to anything that was remotely related to rhythm, repetition, or duration, they showed little interest in their own breathing, which thoroughly limited their ability to report their findings.

Symptomatically, they could only speak in line language, lost as they were in their own brand of monoglossia. Breathless and half-crazed, barely back from their counter-cartographic apneas, they were awaiting our translational assistance. Problem was, our best translators were also the worst. To translate efficiently, say, an utterance made by one of us in line language, to convert a depleted comrade’s spatial images into temporal sequences, a whole lot of loving intuition was required. So, we would pair those of us united by a special bond, usually a heartbreak. Our problem with love was forcing us to navigate highly unpredictable journeys in intellectual empathy.

On day 87, I was assigned to perform a simultaneous interpretation of my beloved comrade’s commentary on Cmap n°0-RT-243864. It was a cognitive map of global warming that we all knew was poorly elaborated, confusing in its orientations, and, for these reasons, probably crafted by the Alternative Cartographers Associates on a subaverage open-source software in the early 2000s. We were all clearly upset to be devoting any time at all on such a prodigiously inefficient instance of liberal mapping, but our depleted comrade had grown obsessed with the details of the map. They were zooming in on one pixel to try and demonstrate—in arrow dialect, of all languages—that the liberal origin of the map was a strategic simulation. My broken love for them allowed me to see that they had sunk in a Baudrillardian delirium and were trying to get out of it through early postmodern methodologies, using that one pixel as an Aleph from which truth would be unveiled as totality and origin as mere absence.

Unfortunately, none of this knowledge, compassionate or theoretical, was helpful. My skills in arrow dialect were far too rudimentary and the specialists among us were thoroughly useless, caught up in their own zone of stubbornness, intellectually paralyzed by the simple possibility of the liberal provenance of the map. Not uncharacteristically, we were on the verge of wasting our breath on that one recurring debate that divided us like a dash, between those who proudly believed in the purity of the origins, and those for whom the proximity between the proper and property could only be subsumed by properly repurposing the properties of the enemy. That debate had always led us to dark schismatic aporias only, which inevitably triggered in us bad class struggle memories and severe divorce trauma.

Meanwhile, our depleted comrade was getting frustrated not to be understood, and I was trying hard to intuit why they would have chosen the arrow dialect to decode the map of global warming, instead of more traditional trends in line language. The heartbreak strategy paid off, at least at first. Lovesick over the black circling our comrade’s eyelashes, up and down, I figured that they had started from the implicit premise of a metonymic relation between the arrow dialect and the red arrows on The Naked City, a Situationist map of Paris. Testing the subtitle as a possible clue (“Illustration of the Hub Hypothesis in Pyschogeographics”), I located the three main hubs of the map—the Latin Quarter, Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and the Marais—which lead me strictly nowhere. I ended up inferring that our suffocating comrade wanted us to isolate the hub as the paradigmatic configuration of our respiratory hellscape. From there, we were able to recompose a cognitive map that we titled The Naked Lungs: Illustration of the Hub Hypothesis in Racial Capitalism to show and project the distribution of suffocated life from early settler colonialism to exoplanetary extractivism.

The process was going well, until my broken love for our depleted comrade kicked in. I started mistranslating and it took a while—well, it took another comrade’s broken love for my broken self—before everyone realized that I was now mentally superimposing the Map of Tender onto the Situationist map on which we had projected Cmap n°0-RT-243864, creating a palimpsestic mess that made us lose track of the matter at hand.

“Hey, you!” my heartbroken comrade interpellated me. “Time to update and decenter. First you reduced the interpretation of the red arrow to some Germanopratin, self-referential play on the urban dérive. Meanwhile, it was clear that, if our sister’s diasporic psyche was drifting, it was in the streamline of the Middle Passage again, along with thousands of dozens of waterfilled lungs and choked memories. Your Beaubourg Hub? Their Elmina. Your Aleph? Their Aleph. Their Door of No Return. R&R.”

“Fair enough,” I acknowledged. “Did you say ‘Second’”?

“Well, now, you’re taking the weirdest and most misleading of cartographic detours to a 17th-century artifact in pre-affect theory, getting us stuck in all the murky waters and the Coviddy bushes in town. ‘Indifference Lake’? ‘Tenderness’ ‘Inequality’?! Seriously?”

“What about ‘Inequality’?” I asked.

“Not an affect,” she scolded. “Structure of all affects, if anything.”

“Aren’t we post- and beyond?”

“We have no distinct sense of where we are or are not,” she concluded.

On day 90, everything stopped. By “stopped,” what I really mean is that everything resumed. Business as usual. Retour à la normale. Pretty much how we had anticipated it, not without a fair amount of dread. We were able to enact and communicate our love to each other again. The apparatus, along with its usual techniques of counterinsurgency, disciplinary and biopolitical, regained some workable level of legibility. Breathing was working just fine again—unless gagged, or stifled, or kneeled upon, or just as racially exposed to horrendous air quality. Our radical meditation workshops could resume safely, the world could end again. And every now and then, a podtag still appears on the privatized walls of certain neighborhoods…