Breathing with Mountains

For Sydney Levy, who brought me on board.

Geologic Aspirations1A slightly longer, open access version of this essay is available online at http://substancejournal.sites.lmu.edu/breathing-with-mountains/index

Stone breathes within nature’s time cycle…. It begins before you and continues through you and goes on. Working with stone is not resisting time but touching it.—Isamu Noguchi

Under the suffocating circumstances of lockdown, COVID conditions inevitably wafted their way into the stoned thinking of Pierre Jardin.2See Paul A. Harris, “Stoned Thinking: The Petriverse of Pierre Jardin,” SubStance, vol. 47, no. 2, 2018, pp. 119-148. The pandemic atmosphere made air apparent, and breathing became personal, political, and planetary. People sought perspective in sometimes surprising ways. While many turned to the Stoics, Jardin turned to stone. Suspending his disbelief in “The Hammock of Relaxation” (fig. 1), Jardin stretched his imagination, and set himself adrift in diffuse reveries of rocky respiration.

The Hammock of Relaxation. Pebble on book cover.

Jardin composes a life centered in absorbing stone(s), encompassing both a physical process of soaking in a substance slowly and psychological experience of becoming engrossed in it. He feels alive with stone and stone alive in him; literally and metaphorically, he has spent hours looking at stone, listening to stone, and touching/being touched by stone. But he had never seriously considered breathing stone. Immediately, a slew of questions arose: Do rocks breathe? Do mountains? Does the Earth? What would it mean to breathe with a stone, or with the planet? Jardin’s pursuit of lithic and lithospheric respirations came to comprise his geologic aspirations, which are set out here.

Aerial Imagination

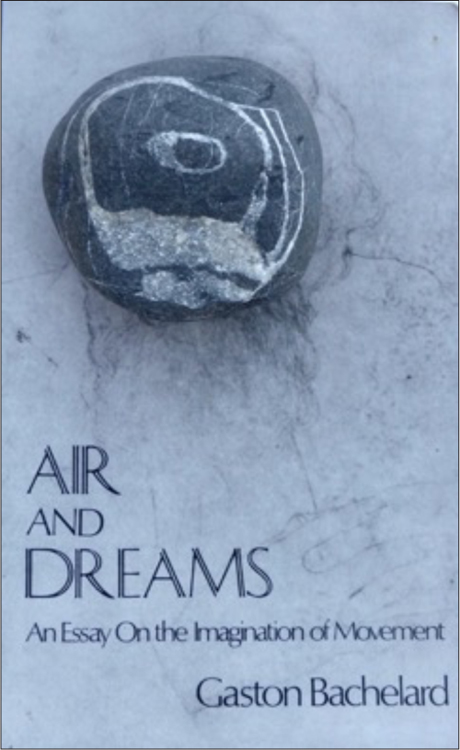

Pierre Jardin’s geologic aspirations took inspiration from Gaston Bachelard’s aerial imagination, as described in Air and Dreams. Accepting Bachelard’s invitation to “listen to nothing but our own breathing…, to become as aerial as our breath…” (Bachelard, Air 241), Jardin set about inventing a regimen of contemplative breathing exercises. To do so, he took up what Bachelard terms the “search for a thought hidden under expressive sedimen,ts, [in which] a geology of silence is developed” (Bachelard Air, 251). The question was, what “expressive sediments” should Jardin mine in this quixotic quest? What materials and mental modalities would precipitate a “geology of silence”?

In order to meld minds with Bachelard, Jardin placed a pebble on Robert Lapoujade’s pencil portrait that graces the book’s cover (fig. 2). The results were alchemical: the cobble transmuted into a philosopher’s stone, opening Bachelard’s third eye; the rock launched a basalt on Jardin’s senses that produced an “intoxication of aerial imagination raised to its cosmic role” (Bachelard, Air 241). A gesture as simple as placing a rock on a book crystallized new quartz-veins of thought. What follows are Jardin’s experiments with a variety of “expressive sediments,” a series of multi-scalar meditations and various instantiations of lithic respiration.

Aerial Basalt on the Senses. Pebble on book cover.

Atmospheric Compositions

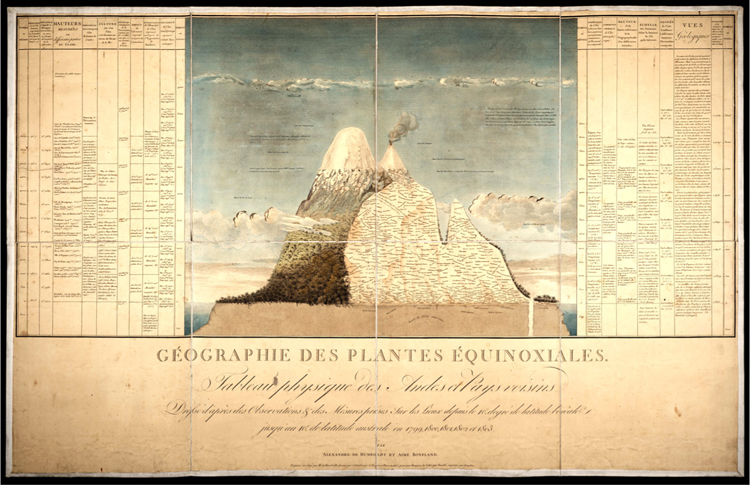

Pierre Jardin’s geologic aspirations began with a Composition of Place, a meditative technique deployed in the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola. Loyola stipulates that “for contemplation or meditation about visible things… the ‘composition’ will consist in seeing through the gaze of the imagination the material place where the object I want to contemplate is situated” (Ganss 47). Taking “Breathing with Mountains” as the “object” of contemplation stretches Jardin’s imagination to a geologic scale; its “material place” is the Earth’s atmosphere, or more specifically, its lowest layer, the troposphere.

To facilitate his meditation, Jardin scales Earth down to a stunning serpentine stone, which he has mounted like a globe. Holding the stone and breathing slowly, Jardin can visualize the troposphere as the thinnest of films on the rock’s surface. In his active imagination, the bumps, furrows, and ridges in the rough rock texture evoke the constant crumpling of the lithosphere caused by drifting and crashing tectonic plates.

With the stone standing in for Earth, Jardin suddenly becomes a geologic giant representing Anthropocene humanity. As his exhalations cloud the stone, Jardin considers how Anthropogenic expirations are changing the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere. An index of human impact is provided by Clément Poirier, a member of the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG), who calculated the rate of rise of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from the earth/ocean system over the past 15,000 years. The resulting graph charts graphic results: an almost-horizontal line that, at its right-hand end, turns into an almost vertical line. The steep increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide begins around 1850CE, the onset of the Industrial Revolution and burning of fossil fuels; at the onset of the Anthropocene in 1950CE, it becomes a straight-up sign registering a massive amount of CO2 humans have emitted into the air.

Earth Globe Stone.

This information gives Jardin’s Composition a turn: how much CO2 is in the atmosphere, and how would one visualize it? Jardin finds an answer in a powerful collaboration between geologist Jan Zalasiewicz and artist Anne-Sophie Milon. Through a series of calculations, Zalasiewicz arrives at a startling image, for which Milon provides a haunting illustration (fig. 4):

Although we intuitively think of gases as weightless—indeed, ‘as light as air’—they do possess mass. That ‘extra’ human-produced carbon dioxide weighs about a trillion metric tons; that’s about the same as 150,000 Great Pyramids of Khufu, hanging in the air above us. Considered as a layer of pure gas around the Earth, it is about a meter thick, and so waist-high to an adult but already over the head of a small child. As it is now thickening at about a millimeter a fortnight, it will, at current rates, keep up with or outpace the growth of that child.”

Anne-Sophie Milon, The Exhaust (2018).